Alexa Fredston says that she doesn’t have “an origin story” about being at the beach and having an ‘Aha!’ moment. She thought about being a doctor, but later decided to study natural resources or ecology because she felt drawn to protecting biodiversity- helping both planet and people.

Seeing How Humans Are Changing the Planet

In college at Princeton University, Alexa majored in Ecology and Evolutionary Biology. She spent six months in Panama doing research as part of her major and it was there that she had her first exposure to research. She saw first-hand how humans are changing the planet. Before starting her PhD, Alexa worked for two years at the Environmental Defense Fund where she worked on fisheries management.

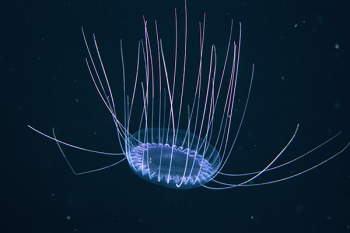

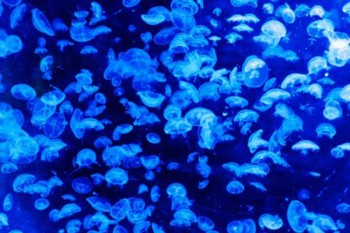

Climate change was one of the issues on everyone’s mind when Alexa was a student. Humanity’s impact on the planet is clear with climate change. In graduate school at UC Santa Barbara she focused specifically on fisheries issues. Because of a warming ocean, fish populations are moving towards the poles, which presents a challenges for fisheries management. The issue is both relevant to how humans relate to the ocean and is a deep scientific question: there is so much we don’t understand about where species are and why.

Research

On her website, Alexa says, “I aim to improve how humans understand, manage, and use nature. Most of my research investigates marine biogeographic patterns and ecological processes, how human influences are reshaping them, and how well their dynamics can be predicted with models.” She is interested in “ecological forecasting”, which determines how well scientists can predict what a species will do in the future based on data sets from the past and present.

Recently Alexa, along with colleagues, published the results of a study ”that found that marine heatwaves in general have not had lasting effects on the fish communities that support many of the world’s largest and most productive fisheries.”

Not as Bad as We Thought

Using government data, the study focused on fish (like rockfish) important because they are primary targets of bottom trawl fisheries. These fisheries tow nets just above the bottom. And the fish don’t have a migratory life-cycle. The study found that fish don’t decline in abundance or show changes in community composition after a heatwave. “There is an emerging sense that the oceans do have some resilience, and while they are changing in response to climate change, we don’t see evidence that marine heatwaves are wiping out fisheries,” said Alexa.

Current Work

One project Alexa is working on now is about rocky intertidal invertebrates in California. She is trying to forecast which species will be able to migrate north when the ocean becomes too warm where they currently live.

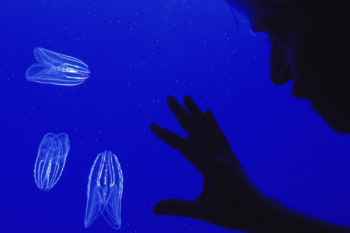

Pt. Conception, off Santa Barbara, is a focus because the transition between northern and southern temperate marine animals occurs there. Alexa thinks that the currents around Pt. Conception prevent some marine invertebrate larvae from getting around the point and moving north. Alexa and colleagues are mapping currents in real time to understand seasonal patterns. They are also studying Environmental (eDNA), which is the “pool of genetic material that can be collected from an environmental sample.” It’s like nature’s fingerprint, showing what lives or is just passing through that spot in the ocean.

Scientists worry that some rocky intertidal invertebrates have a northern range edge like Pt. Conception that they can’t cross: they may get stuck in water that’s too warm to survive. Some scientists have proposed it may be possible to seed areas to the north with larvae, thereby moving some species north.

Tools to Help the Future

Alexa is excited about harnessing large data tools and AI to answer hard ecological questions. In the past it was hard in ecology to have any big data sets. Remote sensing has changed that. She is trying to harness new tools to detect relationships in ecosystems and to predict how they will react.

Data and Hope

When teaching, Alexa witnesses that college students do have climate anxiety and are grieving about the climate. They feel that humanity has given up and tend to think that climate change is a lost cause. But data shows that society has more optimism. She says that there’s a lot to be hopeful about: people are willing to take action personally and institutionally to mitigate and reduce emissions.

The planet isn’t on the path to get to 4-5 degrees of warming. We can do a lot better, and the actions we’ve taken have made a difference.

Alexa wants students to know “there are more jobs that intersect with a goal to help the environment and society than they imagine — from engineering to teaching, from installing solar panels to working in government compliance. There are many exciting ways to make a difference in climate change.”