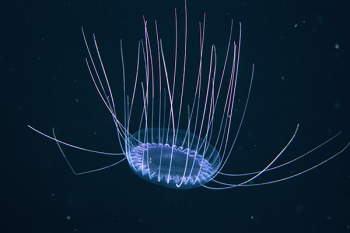

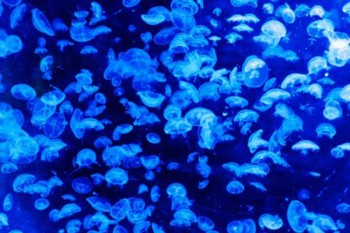

Climate change is not just causing global warming, it’s also causing ocean acidification. Both are due to too much carbon dioxide (CO2) in the atmosphere, which has increased at an alarming rate since the industrial revolution. “The acidity of the ocean has increased by about 25% since before the Industrial Revolution, greater than at any other time within the last two million years.” As the ocean absorbs CO2, it combines with seawater to form carbonic acid, making the ocean more acidic.

Studies show that acidification will harm organisms that rely on carbonate-based shells and skeletons, are sensitive to acidity and organisms higher up the food chain that feed on these organisms. This has ramifications throughout entire ecosystems. The scary part is that we can’t predict how or when they will be impacted.

For shelled animals, a more acid ocean means there are fewer carbonate ions, which are critical for shell building. Some animals will be able to adapt; some others may not.

We Love Our Shellfish

For as long as people have lived near the ocean, we have gathered and eaten shellfish. What do changes in the shells of shellfish mean for those who have benefitted from an abundant food source and way of life mean?

For many Indigenous communities, culture and nature are synonymous. In Washington and Alaska, coastal native peoples’ lives are still very connected to the ocean. They depend on clams and gooseneck barnacles, to name a few.

Indigenous Identity: We are the Ocean, and the Ocean is Us

For the Makah people living on the northern tip of the Olympic Peninsula, shellfish are essential to their lives. Their harvesting of shellfish from the coast has been done intergenerationally ensuring children pass the knowledge and traditions generation after generation. For Chad Bowechop, Makah Tribal Councilman, “…ocean acidification is not simply a physical phenomenon to be studied or measured; it poses a profound risk to community’s spiritual well-being, cultural practices, and identity.” Chad says, “We’re a natural resource tribe–that’s our wealth. We are the ocean, and the ocean is us.”

Combatting ocean acidification is not merely a scientific exercise, nor conservation simply for the sake of conservation. For the Makah, “meeting the challenges of climate change is a cultural, spiritual, and ancestral mandate. At its core, protecting the health of Makah lands and waters is a battle for their very identity.”

In the last several years, the Makah Tribe has launched several initiatives and policy efforts that aim to understand ocean acidification’s impacts, produce creative solutions, and identify tribal sovereignty, resilience and community priorities.

The Makah are developing an ocean acidification action plan, which identifies and addresses the profound impacts of these changing ocean conditions on the tribe in order to best meet the specific cultural, spiritual, and physical needs of their community. The tribe, through their Fisheries Department, also conducts research and monitoring related to acidification.

The Olympic Coast National Marine Sanctuary was designated an ocean acidification “sentinel site,” where climate change monitoring and ocean acidification research is conducted to enhance understanding of the Sanctuary’s natural, social and historical resources and how they are changing. The four tribes along the Olympic coast –the Hoh, the Makah, the Quileute, and the Quinault Indian Nation co-manage marine resources along with state and federal managers. The tribes’ continued well-being depends upon access to healthy and sustainable marine resources that the U.S. government is obligated by treaty to protect. The four tribal nations are on the steering committee for the sentinel site.

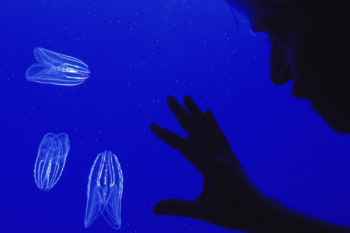

Indigenous biologists from several of the tribes are involved in ocean monitoring projects. There is a network of sensors installed in several nearshore areas in Puget Sound and on the coast. The sensors measure changes in marine chemistry and can be used to evaluate potential impacts on marine organisms. The scientists are concerned that all of the climate change stressors on shelled animals will lead to more frequent die-offs.

Further down the Pacific coast from the Makah are the Quinault, who depend on razor clams for sustenance and income. While ocean acidification has impacted Pacific Northwest oyster hatcheries already, so far there are no direct impacts to razor clams. Climate change is…”a multi-stressor problem,” says Joe Schumacker, a marine scientist with the Quinault Indian Nation. “We have multiple issues: warmer waters, less oxygen in the water, and now combining that with ocean acidification is a triple whammy. If we get a perfect storm of bad events, that can wipe out an entire shellfish population. That’s when we’ll really feel this.”

Other tribes along the Washington coast are participating in monitoring the increasing acidification. For example, The Jamestown S’Klallam Tribe wants to know how ocean acidification might be affecting shellfish in Sequim Bay. The tribe manages more than 60 acres of shellfish farms for commercial, subsistence and restoration purposes, including geoduck, littleneck and manila clams, and Pacific and Olympia oysters. They depend on the shellfish for subsistence, their economy and cultural practices.

In the face of dwindling shellfish resources, Swinomish (in Washington) and First Nations of Canada are reintroducing clam gardens, a traditional maricultural practice, which will ensure access to traditional food and harvest practices if there are die-offs of natural clam beds.

For more general information on ocean acidification, NOAA has a page.