Andrew Kim grew up as an inner-city kid in Los Angeles’ Koreatown. He never spent any time in or around the ocean. As an undergraduate at UC Santa Cruz, he was trying to figure out what to do, a bit at loose ends, thinking of being a music minor. While leafing through the class catalog, Andrew saw a kelp forest ecology class that included diving at Hopkins Marine Station in Pacific Grove. He started from zero experience in ecology and had never been scuba diving when he started diving in the kelp forests of Monterey Bay.

Andrew felt magic while diving in the kelp forest; “being in the kelp cathedral” was the closest to a spiritual experience that Andrew had ever had. He hasn’t stopped diving in the “kelp cathedral” since that class in 2009.

Like many students, “what’s after college?” was a question for Andrew. He got his scuba diving instructor’s license and taught scuba in South Korea where his parents are from. After returning to this country, he took a job at the Monterey Abalone Company on the Monterey wharf. In spite of its name, the farm not only raises abalone but collects marine organisms for researchers: Andrew both collected and managed their collection. This put him in touch with scientists across many disciplines. He was living in and on the water working for a business that depends on healthy kelp. It was a dream job: Andrew lived and breathed the kelp forest for six years, and, he says, “got to live in what felt like an Ed Ricketts/John Steinbeck fantasy.”

In 2019 Moss Landing Marine Lab received funding for a variety of aquaculture-related projects: bull kelp restoration, white abalone aquaculture, scallop larviculture, and multi-trophic aquaculture research and education. Researchers at the lab approached Andrew to start their projects. He spent about half his time working on bull kelp restoration in Mendocino, which involved culturing bull kelp at all life stages, and diving to monitor kelp outplants and conduct restoration research in the field. The rest of his time he spent working on the other aquaculture research projects.

Sunflower Star project

Then late in 2021 during Covid, a man named Vince Christian wanted to talk about the sunflower sea star, Pycnopodia, and aquaculture. He was a lifelong diver but didn’t have any background in aquaculture. The problem he wanted to address: sea star wasting disease that started in 2013 had decimated populations of the sunflower star up and down the west coast. At that time only Friday Harbor Lab in Washington was attempting to grow sunflower stars. Vince established a non-profit, proof-of-concept lab to establish protocol in his Pebble Beach garage. It was a community-driven effort, which allowed it to work nimbly and really get going on the lab.

The project was suited to Andrew’s aquaculture knowledge and also touched him personally having witnessed sea star wasting himself. Kelp forest ecosystems in parts of the Pacific coast have collapsed in the absence of local populations of the sunflower star, which are keystone predators of the kelp forest because they have a disproportionately large influence on other species in their ecosystem. Sunflower stars help protect kelp forests from collapse by grazing on sea urchins. This is my passion,” Andrew says, “what would I do without the kelp forest?”

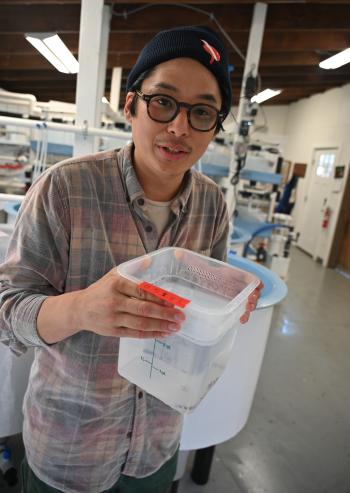

The Sunflower Star Laboratory moved from the garage to its facility in Moss Landing. Andrew is the lab manager, overseeing all the work there. “Sunflower Star Laboratory is a Monterey-based non-profit committed to researching and developing reliable and scalable aquaculture methods for sunflower star (Pycnopodia helianthoides) conservation and reintroduction.” The non-profit started as a “passion” project that had the means, infrastructure and desire.

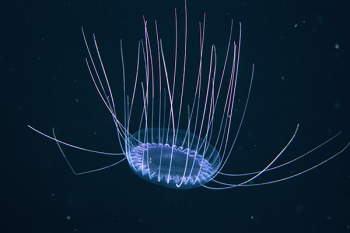

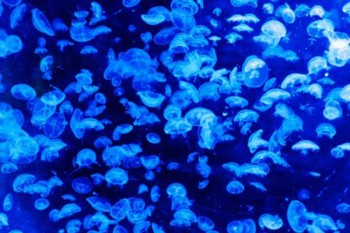

When the recovery project started the sunflower star was essentially extinct in California. But there were still nine individual sunflower stars in captivity: five at the Birch aquarium and four at the Aquarium of the Pacific. The lab coordinated with the Scripps Institute of Oceanography to get embryos from their spawning event at the Birch. The baby sunflower stars from the “Cupid” cohort (named because the event took place on Valentine’s Day, 2024) are what we see in the lab. That spawning event yielded millions of embryos and Andrew was sent one million.

The Sunflower Star Lab under Andrew’s direction is growing the baby stars with the goal of returning them to the kelp forest. The lab is in the research phase now, which is key to successful reintroduction. Andrew wants to make sure that they’re doing things right. For that the lab is doing cryopreservation (freezing) so that they bank away embryos to test for disease resistance or heat tolerance in the future.

Keeping the young sea stars fed is a challenge. So, another big project for the lab is learning what they eat at different stages. The lab is growing microalgae as food for the larval sea stars and sea urchins for the juveniles.

Andrew has found that the sunflower stars can suspend their growth in the beaker. But do they do that in the wild? He wants to know what the sea stars are doing in their early life stages.

They settle on a variety of substrates, but don’t settle without a cue. What are those cues?

Andrew says he would like to tell students thinking of going into science as a career to look to nature: nature is an endless source of inspiration and has lots of answers. Be curious.

In thinking about a sustainable future for the planet one thing Andrew says is that people should be eating more algae. And algae are available around the world. Kelp is one of the first things you eat as a Korean baby. And here Andrew is now, immersed in kelp forest ecology.