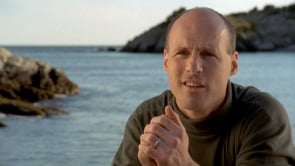

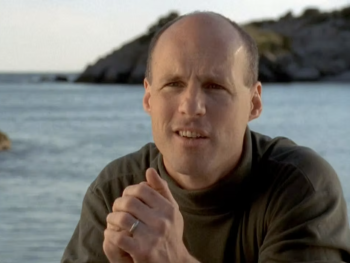

They are creatures so simple that scientists once considered them plants. But they're the critical group to study, if you want to understand motion and behavior. -- Jack Costello

Biologist John (Jack) Costello of Providence College has spent years studying jellyfish. He's found that despite the fact the jellies move almost constantly, they really don't seem to go anywhere. The jellies expend enormous amounts of energy simply pulsing. "That leaves us asking, 'Why would they spend their time swimming?'" Is it to swim, or to eat? Costello also wondered why the creatures possess a shape so seemingly inefficient for swimming. "That round disk shape is probably one of the least effective shapes for forward progress that we can imagine."

Then it occurred to him—perhaps there's more to the pulsing than pure propulsion. Adding tiny, neutrally buoyant beads into a tank of juvenile jellies, Costello tracked and videotaped the pattern of water flow around the pulsing animals. Lo and behold, he discovered that the flow created by swimming actually drew all the beads directly into the capture surfaces and mouth! "That body we think of as being bad or ineffective for forward motion is, in fact, very effective for creating the flow which enables the animal to feed."

About Jack Costello’s Career

John H. (Jack) Costello, Ph.D., is a professor of marine biology at Providence College in Rhode Island where he has been teaching since 1989. He received his Ph.D. in marine biology from the University of Southern California. Costello’s research interests include biomechanics; hydrodynamics and foraging of gelatinous predators; small-scale physical-biological interactions of zooplankton; and feeding and predator avoidance of zooplankton, in particular copepods.

Costello has collaborated on research projects to understand the relationships between form and function in medusae and to understand how this has influenced the evolution of jellyfish. His recent research has focused on how a gelatinous predator—a ctenophore— has shifted its distribution more in response to climate warming over the past 50 years than that of its major prey species, a copepod.