From the Log of the Sea of Cortez, John Steinbeck and Ed Ricketts

“There were great colonies of tunicates, clusters of tiny individuals joined by a common tunic and looking so like the sponges that even a trained worker must await the specialist’s determination to know whether his find is sponge or tunicate. This is annoying, for the sponge being one step above the protozoa, at the bottom of the evolutionary ladder, and the tunicate near the top, bordering the vertebrates…”

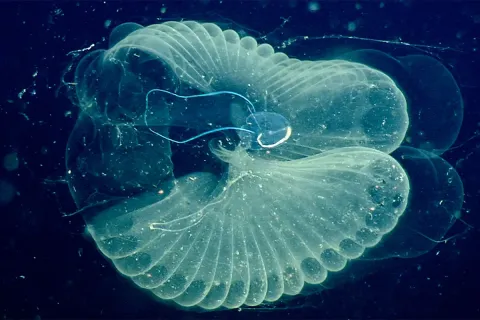

Tunicates are invertebrates without backbones. But in their larval stage they have all four characteristics of chordates: a notochord, which is like a soft spinal cord; a post-anal tail; a dorsal nerve cord; and pharyngeal slits. Their name comes from a thick extracellular covering called a tunic. There are over three thousand species of tunicate living today.

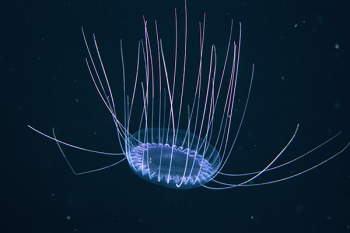

From the deep seafloor to the shallow intertidal, to the midwater zone, tunicates have diversified and occupied every ocean habitat. Some species never move (sessile) once attached to the bottom at whatever depth they live—these are Ascidians, often called sea squirts.

There are two other tunicate groups: the Appendicularians that keep the free swimming tadpole shape and make a mucus net to filter food; and the Thaliacea, the salps, pyrosomes and doliolids that are pelagic (free-swimming) for their entire lives.

Evolution

Because of the four characteristics listed above, tunicates are an evolutionarily significant group of animals as the sister-group to vertebrates (the the one most closely related since both share an ancestral group not shared by any other group), “making them key to unraveling our own deep time origin.” But little is known about the early evolution of the group, for example whether their last common ancestor lived freely in the water column or attached to the seafloor. Since tunicates are soft-bodied, there are few fossils.

In 2023, scientists discovered a 500-million-year-old tunicate fossil in Utah, “which features a barrel-shaped body with two long siphons and prominent longitudinal muscles.” The age of this fossil confirms that the tunicate body plan evolved just after the Cambrian Explosion when most invertebrate body plans developed.

Eating their own brains.

In their larval stages, the sea squirts (Ascidian tunicates) begin their lives looking like a swimming tadpole with the classic chordate characteristics but then settle and metamorphose into a sack-like adult with two siphons. These tunicates live their adult lives attached to a solid surface.

The notochord and part of the brain are digested during this development. A common saying about sea squirts is that they "eat their own brain." But really, only one of the two brains, the one it uses for ocean navigation now obsolete, dissolves.